Giving anaemic cardiac surgery patients a better chance

Researchers explore when it is best to give anaemic patients who have undergone cardiac surgery a blood transfusion.

Published online 31 May 2016

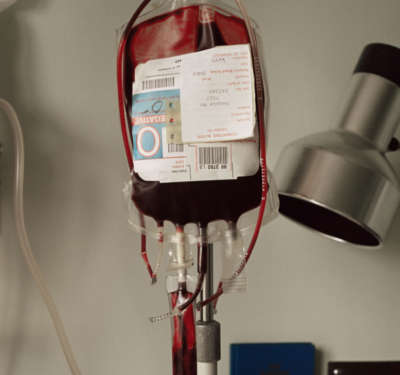

Blood transfusions are one of the quickest ways to improve anaemia, but may come with their own set of problems.

© Image Source Plus / Alamy Stock Photo

In the United States, trauma and cardiac surgery account for nearly 40% of all blood product transfusions. Anaemia commonly occurs as a result of cardiac surgery and has been repeatedly shown to increase patient illness and death.

Yet clinicians are not in agreement about the best time to treat anaemia with a blood transfusion. Although transfusions can help improve anaemia, they can be risky in themselves, causing infections and adverse reactions. Also, exposure to substances in blood transfusions can complicate the outcomes for patients who might receive heart transplants in the future.

Researchers from the Aswan Heart Centre in Egypt reviewed evidence from a recent trial conducted in 17 centres across the United Kingdom1. The trial enrolled patients above the age of 16 undergoing non-emergency cardiac surgery. They were divided into two groups. A “liberal” group was to be given a blood transfusion if their haemoglobin levels fell below 9 milligrams per decilitre (mg dl−1). Doctors would wait longer, however, in the case of a “restrictive” group, which would be given a transfusion if their haemoglobin fell below 7.5 mg dl−1. Based on this, 92% of the patients in the liberal group and only about half of the patients in the restrictive group received a transfusion.

The trial found no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of acquiring serious infections or adverse reactions due to the transfusions. There were also no significant differences in their lengths of stay in the intensive care unit or hospital or in the occurrence of lung complications. Their healthcare costs were also similar. There was, however, a significant difference between the two groups in terms of mortality. Thirty days after the transfusion, 2.6% of the restrictive and only 1.9% of the liberal group died. Ninety days post-transfusion, these figures were 4.2% and 2.6%, respectively.

The study showed that liberal transfusion had an advantage of lower mortality, probably because cardiac patients not treated for anaemia have less reserve to withstand the condition.

The Egyptian researchers concluded that, although the trial was commendable, it still does not answer the question of when to give blood transfusion to cardiac surgery patients. Previous studies have shown that transfusing “fresh” blood collected within the past 48 hours gives anaemic cardiac patients a stronger advantage against transfusion-related illnesses and reactions. This, they say, answers the question of what to give.

Until further research is conducted, “the decision for transfusion of blood or blood products will continue to be an exercise of clinical judgment where factors like patient age, comorbidities and type of operation come into play,” the researchers conclude in their review published in the journal Global Cardiology Science and Practice.Reference

- Afifi, A. & Simry, W. Transfusion Indication Threshold Reduction (TITRe2) trial: when to transfuse and what to give? Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Practice 2015, 61 (2015). | article

DOI: 10.1038/qsh.2016.114